Jan 18, 2022

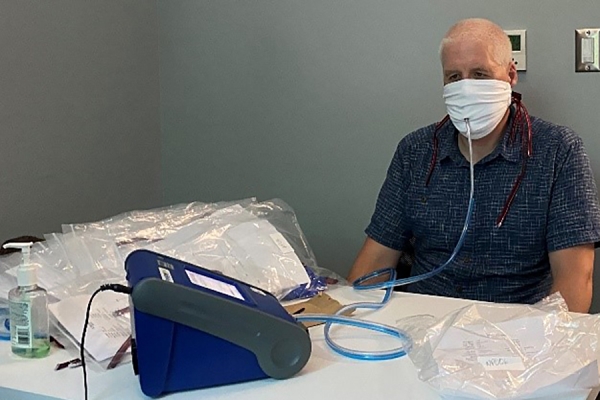

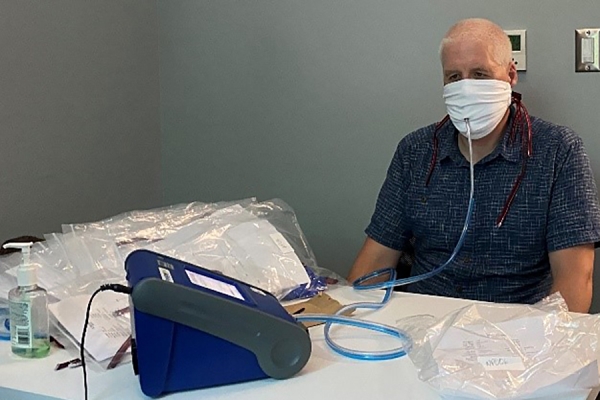

Ken Drouillard tests a two-ply cotton mask made of T-shirt material using a TSI Portacount Fit Tester

and TSI Particle Generator in this photo by Rebecca Rudman.

Wearing a two-ply cotton mask fastened tightly with ties over a basic medical mask offers similar protection to wearing an N95 filtering respirator, research by a UWindsor scientist has found.

In his ongoing research related to COVID-19 and its variants, School of the Environment professor Ken Drouillard is participating in a “mask hacks” study by a team at McMaster University led by researcher Catherine Clase. The study involved testing various masks, combinations of masks, and mask-wearing devices, to find those with the best ability to filter out aerosol-sized particles.

“This is timely information for the public,” said Dr. Drouillard. “Given the high community risk factors posed by the Omicron variant and the scarcity of N95 masks in some provinces, we want to be able to help people use the best mask they have access to.”

Drouillard’s spouse, Rebecca Rudman, is one of the founders of the Windsor-Essex Sewing Force. The group of community volunteers has produced tens of thousands of cloth masks donated to frontline workers and vulnerable populations. Drouillard has lent his expertise to the project and recruited other UWindsor scientists to perform tests on various mask designs and fabrics to ensure the volunteers could produce the most effective masks possible.

Drouillard and the McMaster team performed tests on masks used in combination with those produced by the local group of sewing volunteers. Using a TSI portacounter — the same device used for fit-testing N95 masks — they tested the concept of double-masking: wearing two masks at a time.

The most effective was wearing a two-ply, pleated cotton mask with cotton straps tied snugly over a standard medical mask.

But not all medical masks are created equal, Drouillard explained.

True medical-grade masks are certified by ASTM, an international standards organization. Certified ASTM masks bear the organization’s name on the box. There are three grades of masks available, the L1 being the cheapest and most accessible. The higher grades relate to the mask’s ability to prevent fluids from soaking into them and are generally used only in hospital settings, Drouillard explained.

Drouillard’s testing has shown an L1 alone, worn snugly on the face, filtered out 54 per cent of particles. A two-ply, pleated mask made of high-quality quilting cotton and with ties rather than ear loops provided 55 per cent effectiveness. In combination, with the cloth mask with ties worn over the L1, the filtration rate was nearly 91 per cent.

Drouillard explained that with double masking, it is the medical mask underneath that is doing most of the aerosol filtering. The cotton mask with ties mainly acts to improve the fit of the medical mask underneath. This prevents leakage from the medical mask which can be as high as 50 per cent when worn alone.

This combination costs a fraction of the cost of an N95 mask, even with the initial cost of a cloth mask factored in. Drouillard said testing has shown the two-ply cotton masks can be washed dozens and dozens of times without affecting their performance.

Nearly as good as wearing a pleated cloth mask over an L1 medical is wearing a mask brace — a contraption made of silicone straps you wear around your head over a mask. The filtration rate of such a device worn over an L1 medical mask is 82 per cent.

Masks made of quilting cotton with strings that tie around the back of your head are 55 per cent effective in filtering out particles because they fit more snugly. The same cotton mask with ear loops is only 50 per cent effective in filtering out particles because it has more leaks than the one with ties, Drouillard said.

“Fogged-up eyeglasses when wearing your mask are evidence of air leakage around the nose.”

Knotting the loops on a medical mask and tucking in the excess fabric or fastening the loops onto ear savers or buttons sewn onto the back of scrub caps can also improve performance by making the mask fit tighter. These techniques were less effective than using a cotton mask over a medical mask or using a mask brace, but it still improved performance by up to 15 per cent over normal wearing, Drouillard said.

Drouillard stressed the most important factor in mask design and effectiveness is fit. Even an N95 respirator lacks effectiveness if it doesn’t fit snugly, allowing air to get in around the nose, sides, or under the chin.

“If air can get in around the sides, it’s not as effective,” Drouillard said. “I have to emphasize that the first and foremost important thing you should evaluate while waring your mask is how well the mask fits you.”

Drouillard’s mask research with the Windsor-Essex Sewing Force has been funded by UWindsor’s Office of the Vice-President, Research and Innovation, and the WE-Spark Health Institute, a research partnership involving the University of Windsor, St. Clair College, Windsor Regional Hospital, and Hotel-Dieu Grace Healthcare.

A professor at the Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research, Drouillard is an expert in water pollution and the testing of contaminated sediment. His research is used to inform guidelines for fish consumption.

His work with the Windsor-Essex Sewing Force is an example of how UWindsor experts are lending their research talents to the fight against the pandemic.

Watch a video on the project.

Courtesy: https://www.uwindsor.ca/dailynews/2022-01-17/researchers-mask-hacks-suggest-alternatives-scarce-n95s